It started quite simply, as many times these things do. A quart of soup in a Mason canning jar seems such an insignificant thing but don’t try to say that to a little farming community in the Midwest. They won’t hear you. They remember the story of the prairie schoolteacher who bravely struggled through her first year teaching the three R’s to a gaggle of towheaded kids. They know how she tromped through knee-deep drifts, started fires in a frigid shanty schoolhouse and pressed on through planting season, drought, diphtheria and wildfires. They have been told the tale of her first Christmas, alone in her cabin, scarcely anything to eat when a knock on the door brought a visitor with a hearty gift. They know well that the stew brought her more than nourishment; it was an act of giving that warmed her heart and bonded her to the townsfolk forever. Not to mention, of course, that she married the farmer son of the woman who brought it!

So, today they still keep the tradition of the Christmas jar in that little rift in the fields called home to a stalwart few. Every December, a Mason jar filled with a Christmas remembrance is sent to the newest member of the community, sometimes lavishly appointed, sometimes embellished with homely bits of trim. It might be filled with cookies or caramel popcorn or pudding, but it is always at the very soul of the Christmas spirit itself. The original jar is no more, of course, having fallen victim to careless little hands carrying it on its joyful mission. But hearts in this town are quick to forbear and forgive and a substitute jar hasn’t made any difference to the cheer in which it is received.

This year, the members of the Remington family are to be the bearers of the gift. Theirs is a happy estate, situated on acres of land as flat as pancake, as they say, and teeming with soil that is good for growing things. Mr. Remington’s great-grandfather first staked claim to this property many years ago and his descendants have lovingly worked it since. In summer its fields are full of robust crops of soybeans and wheat and corn, guarded by brilliant sunflowers. In winter, as now, the land lies still and beautiful in frozen sleep, covered with a quilt of snow.

Mrs. Remington has filled the Christmas jar to the brim with homemade goodness, placed a bright scrap of fabric around the lid and tied it with a bit of twine. As she hands it to the noisy twosome putting on coats and gloves and boots, she reminds them of their important task.

“Shelly, remember to take this straight to Miss Calvert’s home. And keep it safe in this basket until you get there.”

“I will, Mama.” Shelly is a pink-cheeked youngster whose pigtails always seem to escape their bands.

“And I know why we’re taking it to Miss Calvert.” This from Tommy, the little brother whose boots betray his fondness for muddy ditches.

“Why, dear?” Mrs. Remington pats his check in spite of the tracks he is making on the kitchen floor.

“Because she is the newest people in our town!”

“It’s person, not people, Tommy.” Shelly shakes her head in grownup dismay.

Mrs. Remington smiles. “That’s all right, Tommy. She is new to our town, and we want her to feel welcome.”

“Because of Grandma Connors and the soup, right?”

“Mmmm-hmmm. It’s a lovely tradition, I think. Now, hurry, children, I want you to be home soon for supper.”

And so out the door they go, Shelly swinging the basket with the jar, Tommy nearly tripping over his dangling boot laces. In a few paces, they have gathered their sleds from the porch and have started down the road toward the smattering of houses they call a town. It isn’t a long walk and certainly not dangerous. The sun is smiling down, though not warmly enough to melt the snow and the neighbors watch the path for children at play. The Remington children are thus carefree and exuberant as they skip onward, unaware that the basket on Shelly’s arm is lighter than before, that the Christmas jar lies in a drift, its fabric trim growing stiff in the cold. They are eager to give the new teacher their gift, to show that this community cares for its own, especially its newest members.

Though there is another district where one might wonder at the truth of this statement. The folks there have no Christmas traditions, other than drink. Their homes are not brightly lit, nor filled with wonderful aromas and happy faces. The Christmas trees there are dismal affairs and the children have little expectation of Christmas morning.

James lives in one of these hovels. He is named for his grandfather, the last good man in his family tree, a man who died serving his country and whose offspring didn’t possess the same firmness of character as he. Little James was born to poverty; life has given him little comfort. He sleeps with his sister and brother underneath a paltry blanket and scrounges for his own breakfast in the chilly kitchen where his breath is warmer than the stove. This morning he thinks about a mug of cocoa. He’s only tasted it once, at a party with his mother when he was much younger, but he remembers the sweet taste and comforting warmth.

And he recalls there were little squishy bits of white floating on the top of the drink. Oh, how he’d love to have a cup of that for Christmas. So, standing in his bare feet on a cold, sticky floor, he naturally turns to a Source his granny told him about – the Father in heaven. In simple terms, he asks for cocoa, please. Then he eats his crumbling crust of toast and runs to find his coat with the short arms and the broken zipper. In a flash, he is dressed as warmly as he knows and out the door. He doesn’t call out to the others in the house; no one will miss him when he is gone.

By chance, he takes the road toward the “other” town. He doesn’t plan to go there; he just wants to walk a ways and view the festive houses from afar. And so, he thinks little about where his feet walk, his eyes are trained ahead, eager for the sight of the happy town.

But, wait . . . he suddenly sees something. Was it an angel who brushed the snow off the little jar and caused the sun to pick up the glint of glass beside him? Who can say? All we know is that the Heavenly Father cares for the little ones and their Christmas prayers are heard and cherished.

It takes James a few minutes to realize what he has found. Mrs. Remington put on the lid tightly and he has to twist it a few times before it comes off. But when he dips his finger in the powdery stuff and brings it to his tongue, a look of delight comes on his face that I think the heavenly hosts must be able to see. And he is quick to pop one of the bits of white into his mouth too. Certainly, no marshmallow has ever been more appreciated. And James turns back toward his pitiful home, the gift held firmly in his little-boy hands. It is proof that granny was right, and he is happy with his wonderful treat. He doesn’t know, of course, that his granny’s prayers are at work nor that Mrs. Remington teaches a Sunday-School class and will soon find him on her visiting rounds through the countryside. He doesn’t understand that sometimes God works through Mason jars and hot cocoa and tiny marshmallows.

And what of the new teacher in town, Miss Calvert? She never will tell that the students dropped her gift in the snow. She smiles tenderly at Shelly and Tommy, wipes their teary eyes and goes right out to buy another jar to replace the one that was lost. It is love that is the real gift after all and that has been delivered in abundance.

And as for the boy from the hovel, well, it will be many years before the full story will be known and by that time, James will be a young minister with a little boy of his own and a heart dedicated to helping others. He will retain a fondness for hot cocoa topped with marshmallows and will be quick to share a cup with anyone he can. Because to his way of thinking, there has never been a gift as full of hope and love as the Mason jar filled with cocoa by Mrs. Remington and dropped in the snow by angels that winter’s eve on the prairie.

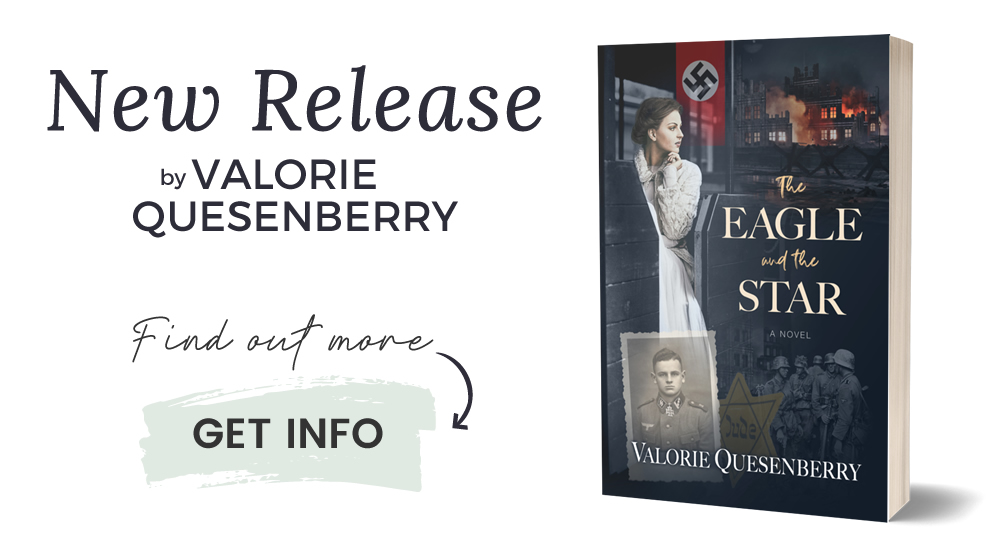

(Copyright by Valorie Quesenberry, 2013. All rights reserved.)